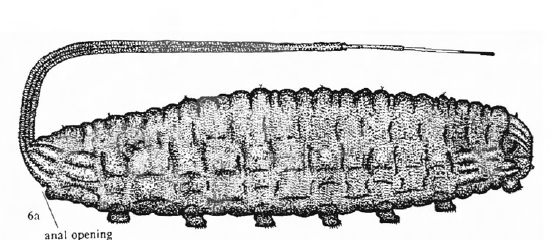

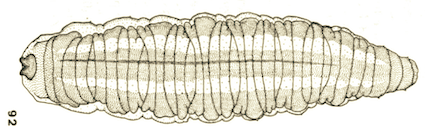

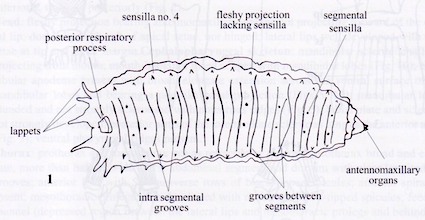

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

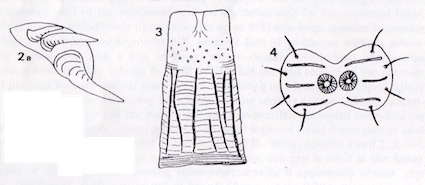

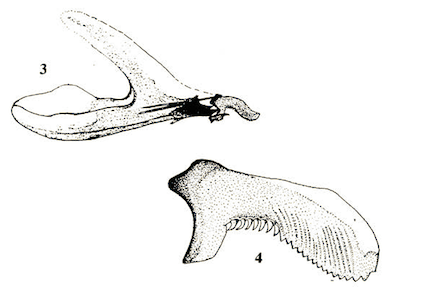

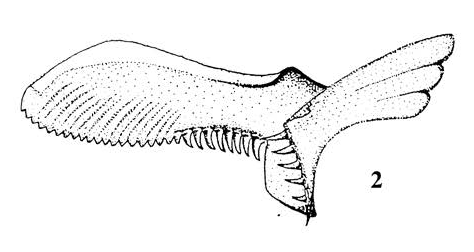

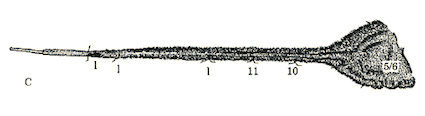

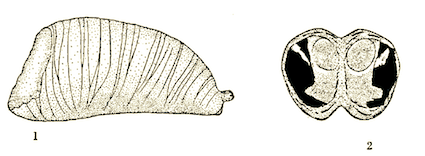

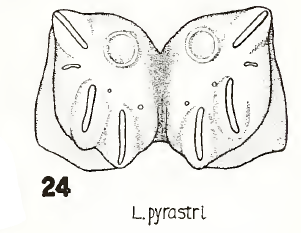

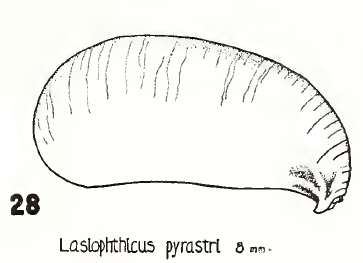

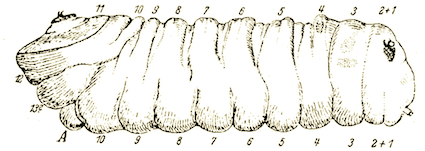

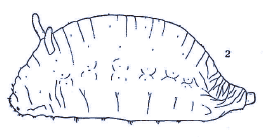

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

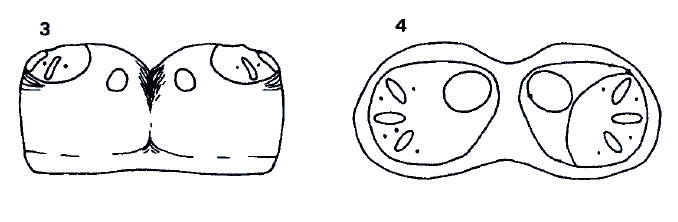

Bagachanova (1990)

Hartley (1961)

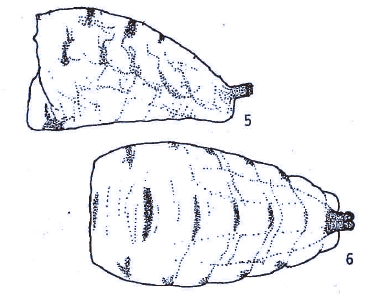

Hartley (1961)

Bagachanova (1990)

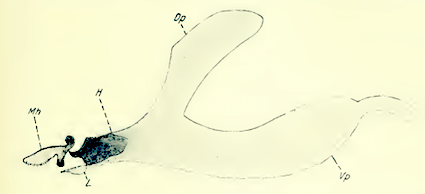

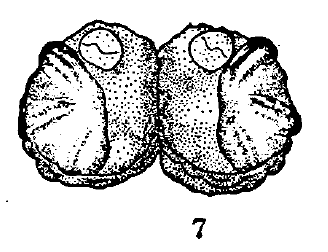

Rotheray, G.E. & Gilbert, F.S. (1999)

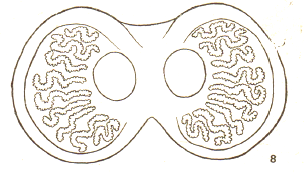

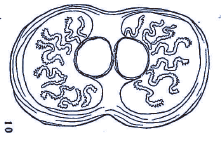

Bagachanova (1990)

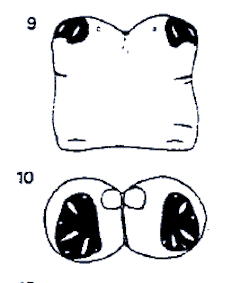

Bagachanova (1990)

Bagachanova (1990)

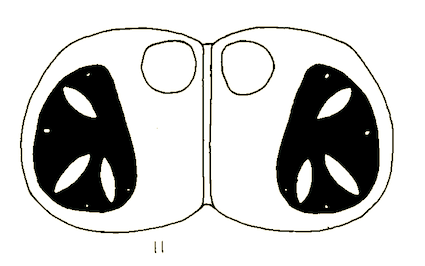

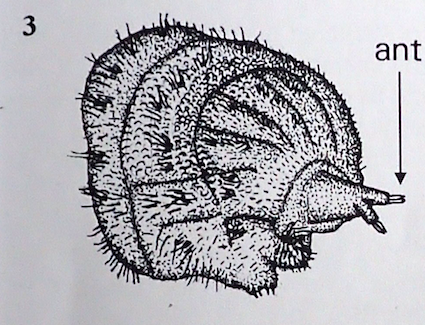

Rotheray (1994)

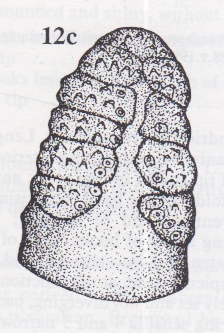

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

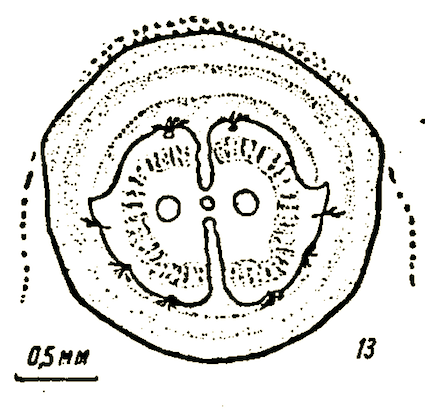

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

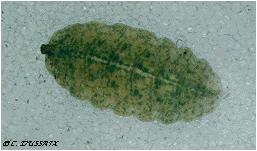

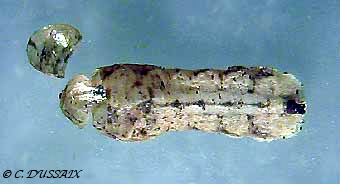

Dussaix, 2013

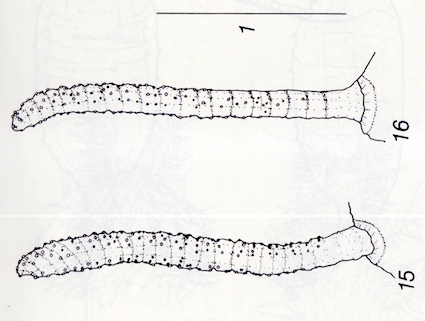

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

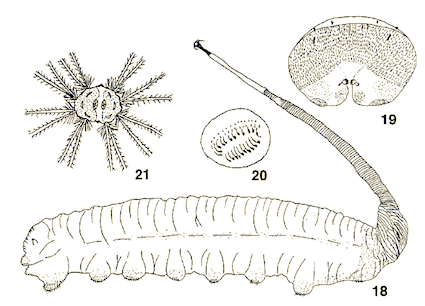

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray & Rotheray, 2012

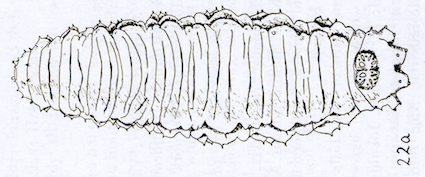

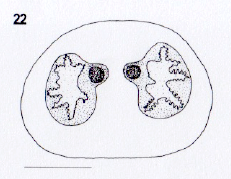

Rotheray et Stuke, 1998

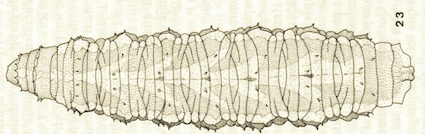

Kassebeer (2000)

Rotheray (1994)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2016)

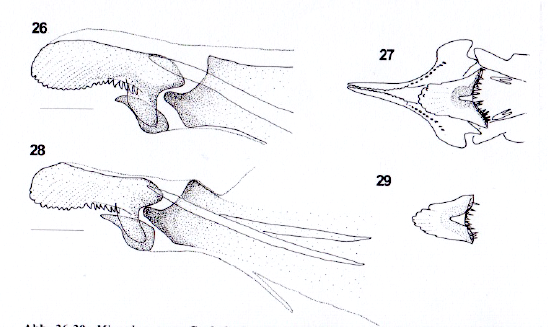

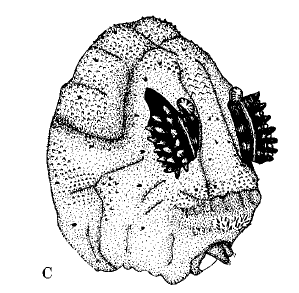

Krivosheina (2005)

Rotheray (1991)

Krivosheina (2005)

Dussaix, 2013

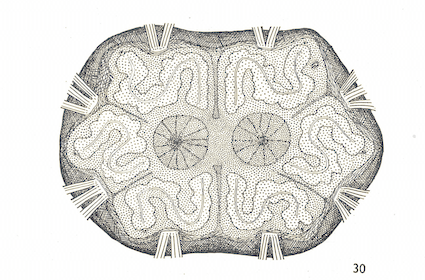

Krivosheina (2005)

Krivosheina (2005)

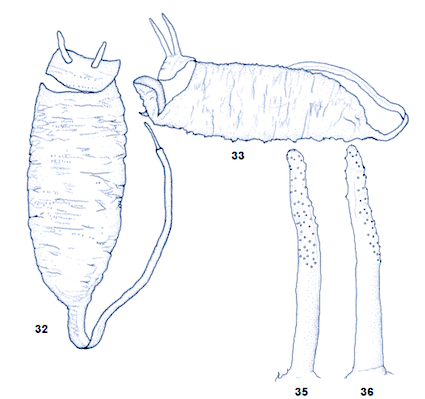

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1991) // Krivosheina (2005)

Rotheray (1991)

Dussaix, 2013

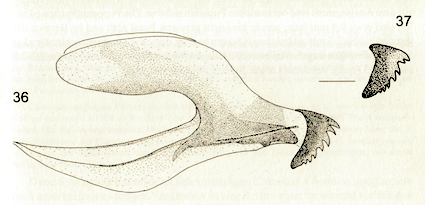

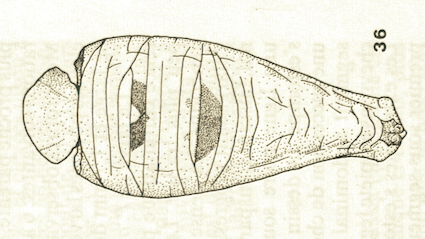

Bartsch et al (2009)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2016)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2016)

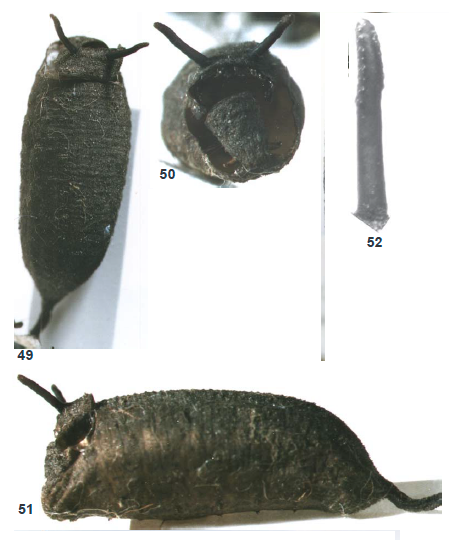

Carstensen, L. B. (2022)

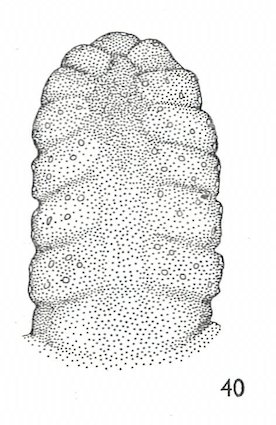

Shparyk and Zamoroka (2021)

Krivosheina (2005)

Shparyk and Zamoroka (2021)

Shparyk and Zamoroka (2021)

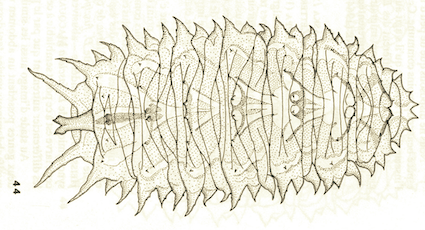

Pérez-Bañón et al (2016) Brachyopa sp. aff. pilosa

Krivosheina (2005)

Rotheray (1991)

Krivosheina (2005)

Rotheray (1996)

Rotheray (1996)

Krivosheina (2005)

Krivosheina (2005)

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

Rotheray et Stuke, 1998

Rotheray et Stuke, 1998

Rotheray et Stuke, 1998

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

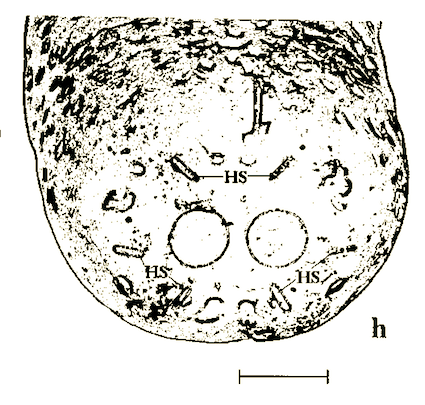

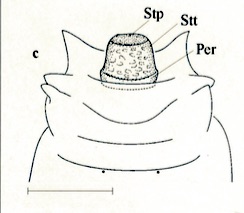

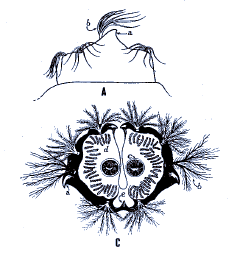

Face ventrale

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

Schmid & Moertelmaier (2007)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994) // Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1991)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert, 2011

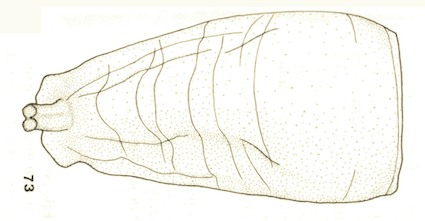

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray & Perry (1994)

Rotheray (1991)

Dussaix, 2013

= Callicera yerburyi

Rotheray (1994)

Dixon, 1960

Reemer et al (2009)

Rotheray & Perry (1994)

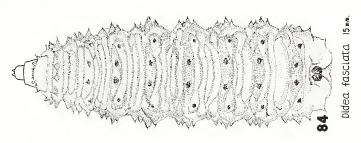

Rotheray (1991) // Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Perry (1994)

Rotheray & Perry (1994)

Dussaix, 2013

Dufour (1847)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Jukes, 2009

Jukes, 2009

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1992

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1992

Dussaix (site web)

Stammer, 1933

Hartley (1961)

Heiss, 1938

Dussaix (site web)

Coe, 1953

Bartsch et al (2009a

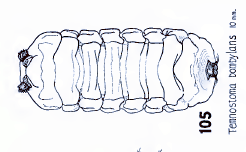

Heiss, 1938

Bartsch et al (2009a)

Schmid & Moertelmaier (2007)

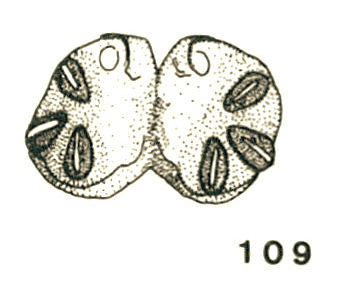

Bartsch, Ståhls & Kerppola, 2010

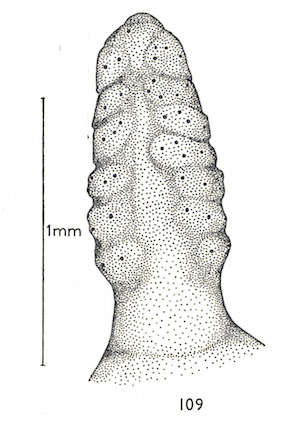

Bartsch, Ståhls & Kerppola, 2010

Dufour (1848)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

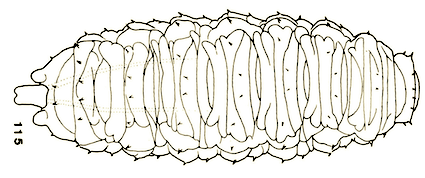

Stuke, 2000

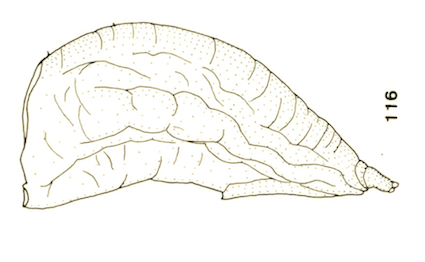

Stuke, 2000

Dufour (1848)

Dussaix (site web)

Ball, Morris & Stubbs, 2008

Bartsch et al (2009)

Rotheray (1988a)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Dussaix (site web)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1991)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Smith (1979)

Smith (1979)

Smith (1979)

Smith (1979)

d'Aguilar & Coutin (1988)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

Stuke, 2000. Cheilosia cf. canicularis (PANZER, 1801)

Stuke, 2000. Cheilosia cf. canicularis (PANZER, 1801)

Stuke, 2000. Cheilosia cf. canicularis (PANZER, 1801)

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Bruun & Bygebjerg, 2016

Rotheray (1990)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Bruun & Bygebjerg, 2016

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dussaix (site web)

Rotheray (1988a)

Stuke & Carstensen (2002)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Ball, Morris & Stubbs, 2008

Rotheray (1988a)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek (1962)

Dusek (1962)

Rotheray (1990a)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Dusek (1962)

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

Rotheray (1999a)

Rotheray (1999a)

Rotheray (1999a)

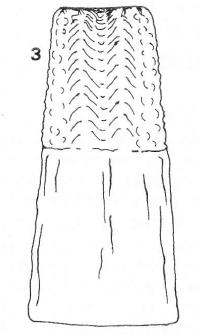

Schmid (1999a)

Schmid (1999a)

Stuke, 2000

Schmid (1999a)

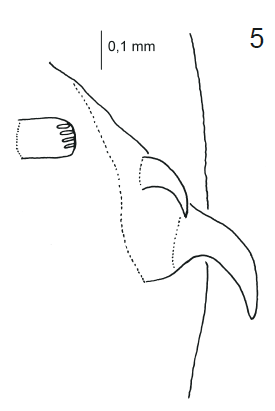

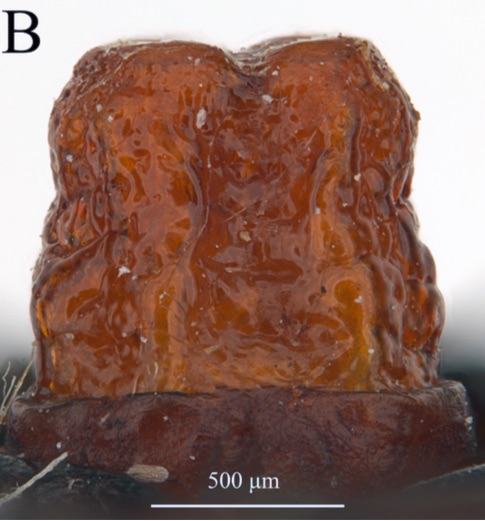

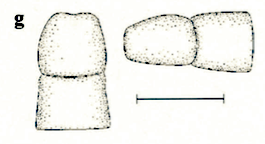

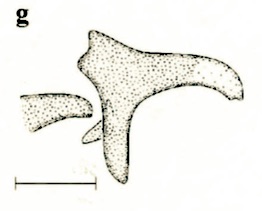

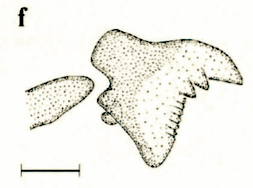

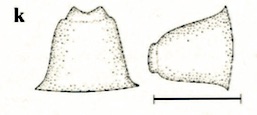

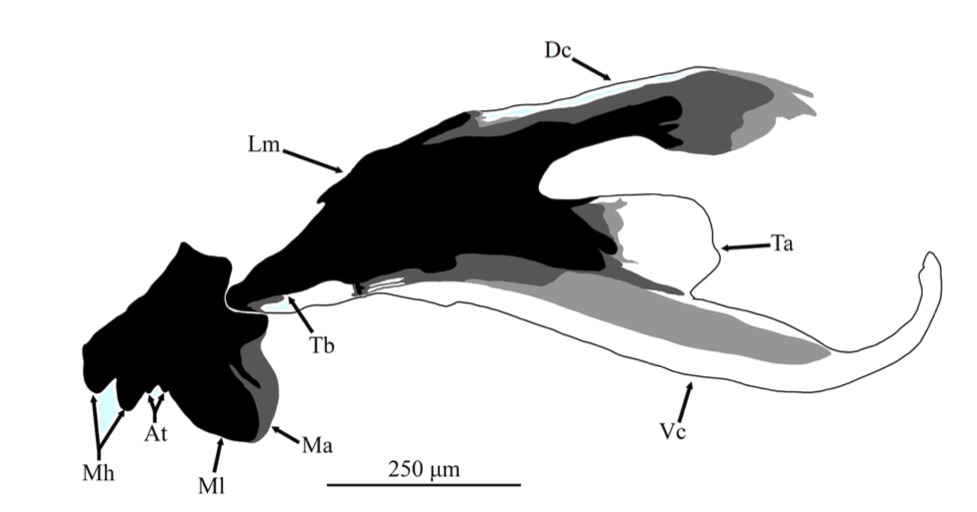

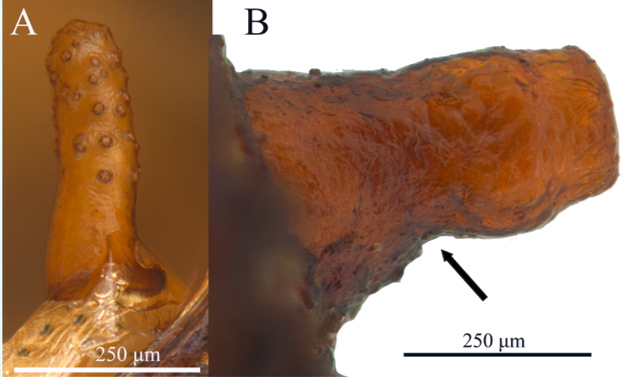

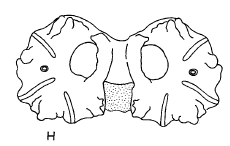

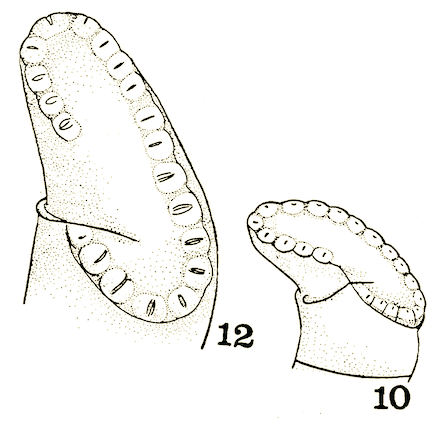

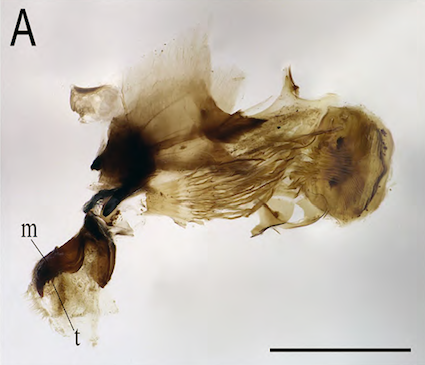

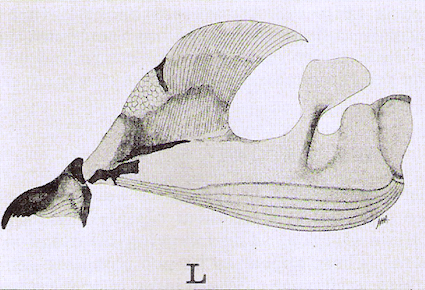

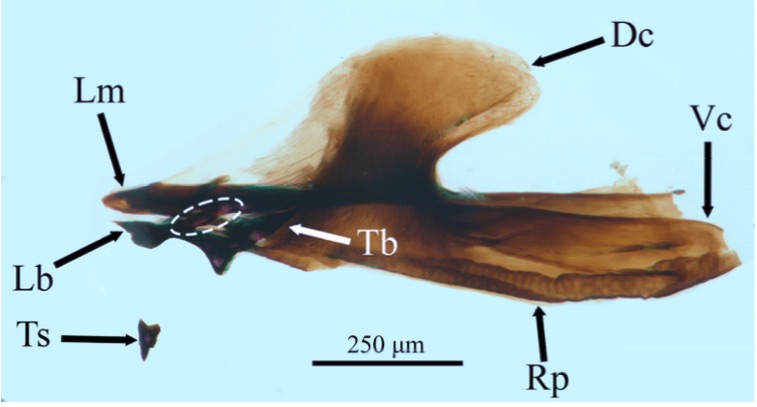

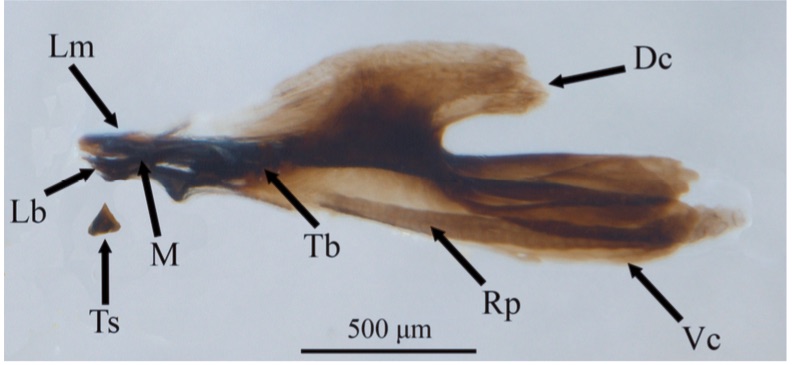

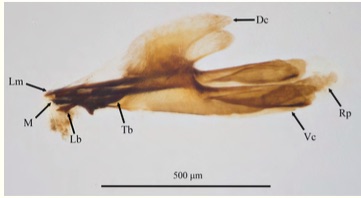

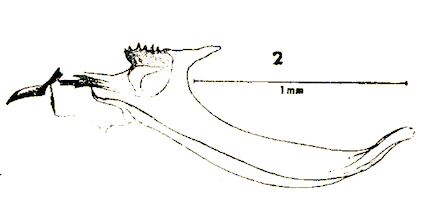

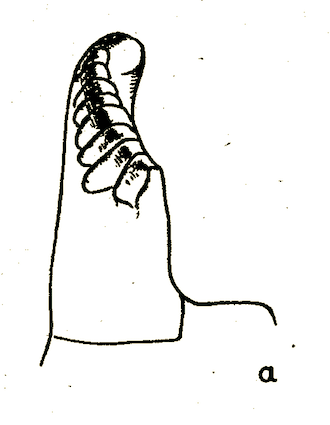

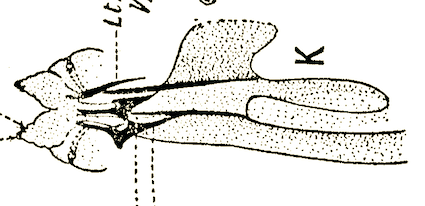

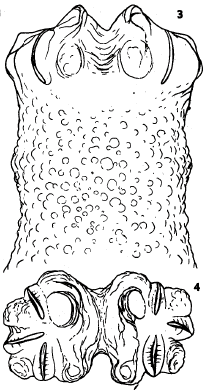

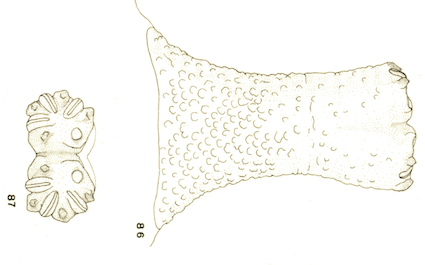

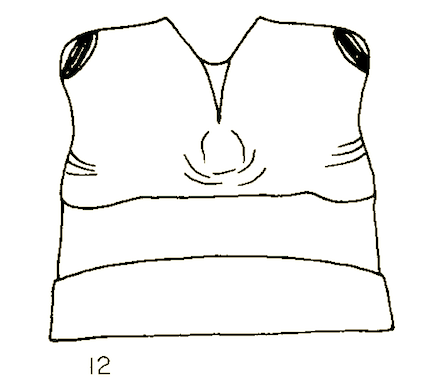

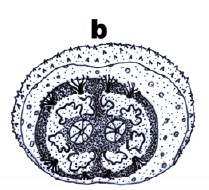

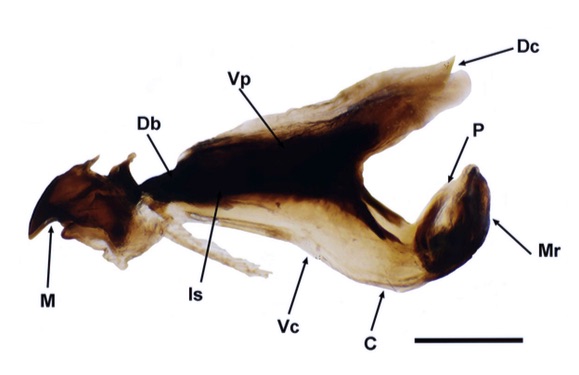

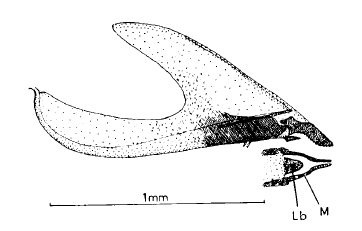

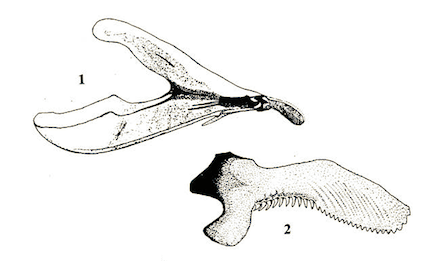

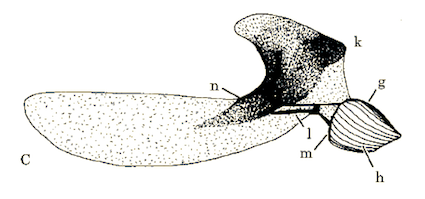

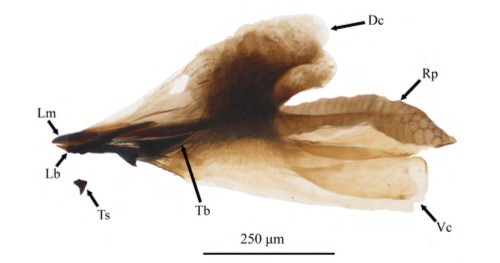

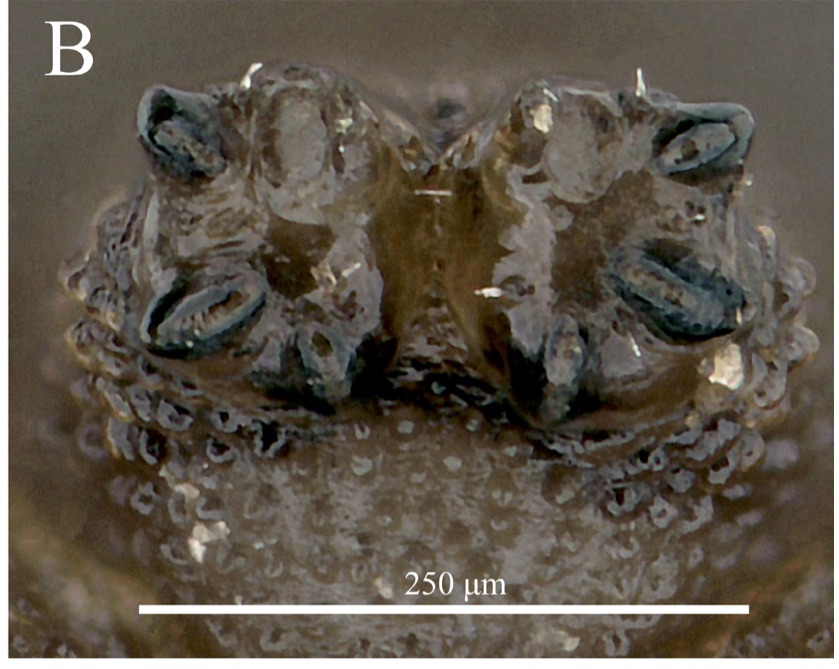

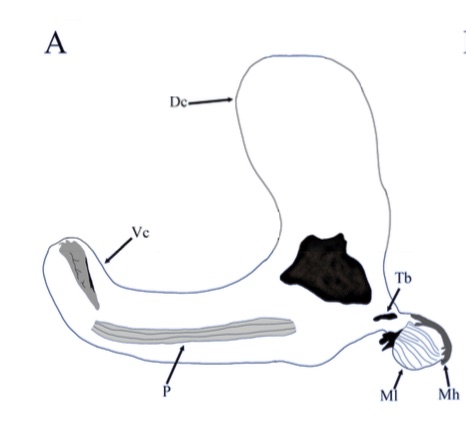

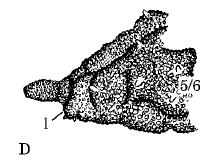

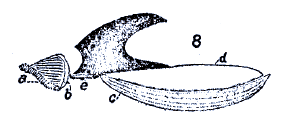

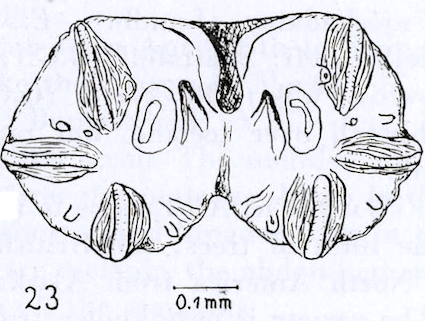

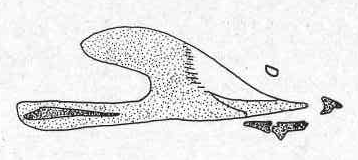

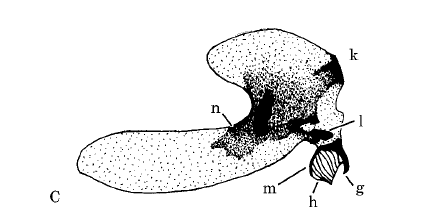

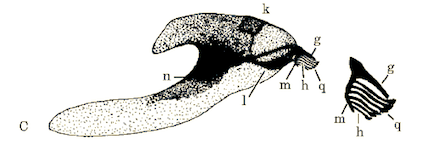

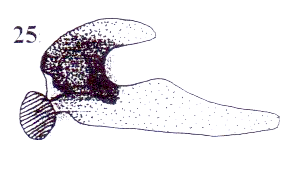

Pièce buccale ex-pupe

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

Stuke & Carstensen (2000)

Stuke & Carstensen (2002)

= C. omissa

Dusek, 1962

Dusek, 1962

Stuke, 2000

Dusek, 1962

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1990)

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Mamaev, 1971

Tragardh (1923).

Bartsch et al (2009)

Tragardh (1923).

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray (1990)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray (1988)

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

Stuke & Carstensen (2002)

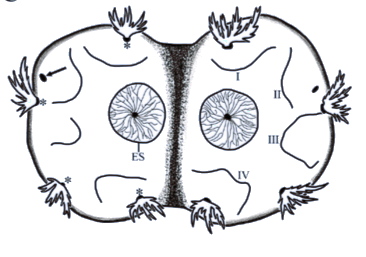

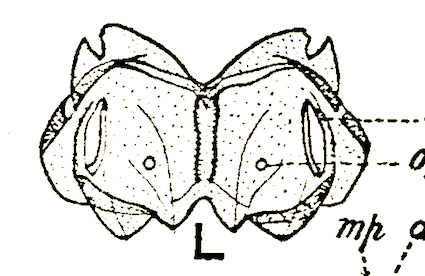

Ventral side

Foster R. (2020)

Foster R. (2020)

Schmid (2000)

Schmid (2000)

Schmid (2000)

Schmid (2000)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Dufour, 1840

Rotheray (1990)

Stuke, 2000

Dufour, 1840

Rotheray (1994) and Rotheray (1988c)

Schmid, 2004a

Stuke, 2000

Reemer et al (2009)

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000. Cheilosia cf. subpictipennis CLAUSSEN, 1998.

Stuke, 2000. Cheilosia cf. subpictipennis CLAUSSEN, 1998.

Dusek, 1962

Rotheray (1990)

Dusek, 1962

Dusek, 1962

Stuke, 2000

Stuke, 2000

Dusek, 1962

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

Stuke, 2000

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

ORENGO-GREEN J.J. et al., 2025

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

Brunel & Cadou (1990a)

Stuke & Carstensen (2002)

Brunel & Cadou (1990a)

Brunel & Cadou (1990a)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

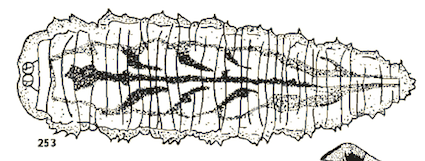

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1963)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

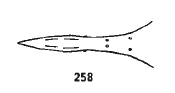

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Speight (1976)

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray & Stuke, 1998

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

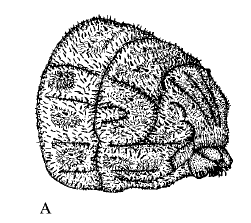

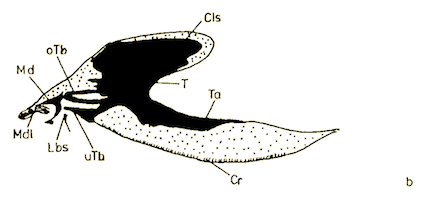

Criorhina berberina (Fabricius), 1805

Rotheray (1994)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray & Stuke, 1998

Ball & Morris, 2013

Rotheray (1991)

Ball & Morris, 2013

Rotheray & Stuke, 1998

Dixon, 1960

Smith, 1989

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Bitsch, 1955

Brauns, 1953

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Dixon, 1960

Scott (1939)

Bitsch, 1955

Scott (1939)

(= D. lunulatus)

? Nielsen et al (1954)

Rotheray (1987)

? Nielsen et al (1954)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1994)

Ball & Morris, 2013

Nielsen et al (1954)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray (1994)

Ball & Morris, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Rotheray (1987)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1967)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Heiss, 1938

Láska, Mazánek & Bičík, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Metcalf (1916)

Dussaix (site web)

Speight (1988c)

Speight (1988c)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Rotheray (1994)

Dixon, 1960

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Brauns, 1953

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013 (Larve en diapause)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Smith, 1989

Mazánek et al (2001)

Dussaix, 2013

Mazánek et al (2001)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mazánek et al (2001)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mazánek et al (2001)

Rotheray (1994)

Mazánek et al (2001)

(= Epistrophe liophthalma)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau (1974)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Mazánek et al (2001)

Dusek & Laska (1959) and Láska, Mazánek & Bičík (2013)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau (1974)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dixon, 1960 // Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Scott (1939)

Bhatia (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Brauns, 1953

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Kula, 1983

Kula, 1983

Geoff Wilkinson et al (2020)

Kula, 1983

Kula, 1983

Geoff Wilkinson et al (2020)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Hartley (1961)

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Lobkova et al, 2007

Hartley (1961)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961) // Dusek & Laska (1960a) // Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Lobkova et al, 2007

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Zalat & Mahmoud, 2009

Hartley (1961)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Bagachanova (1990)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Bagachanova (1990)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2003)

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Nielsen & Svendsen (2014)

Campoy et al (2017)

Dolezil (1972)

Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Bagachanova (1990)

Hartley (1961)

Bagachanova (1990)

Dussaix, 2013

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov and Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Maibach & Goeldlin (1991b)

Dolezil (1972)

Maibach & Goeldlin (1991b)

Dolezil (1972)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2013)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2013)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Hamed et al, 2017

Ikezaki, 1977

Hartley (1961)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2013)

Ikezaki, 1977

Hartley (1962)

Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Pérez-Bañón et al (2013)

Dussaix, 2013

Ikezaki, 1977

Speight & Garrigue (2014)

Souba-Dols G.J. et al., 2020

Souba-Dols G.J. et al., 2020

Souba-Dols G.J. et al., 2020

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-Garcia (1998)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-Garcia (1998)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-Garcia (1998)

= E. tuberculatus

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1994)

Hodson, 1932

Rotheray (1994)

Hodson, 1932

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2017

Aracil et al. (2023)

Aracil et al. (2023)

Aracil et al. (2023)

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2017

Speight & Garrigue (2014)

Ricarte et al., 2017

Ricarte et al., 2008

Ricarte et al., 2008

Ricarte et al., 2008

Ricarte et al., 2008

Speight & Garrigue (2014)

Ricarte et al., 2008

Ricarte et al., 2008

Heiss, 1938

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Smith, 1989 // Dixon, 1960

Dixon, 1960

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Dusek & Laska (1961) // Ricarte et al., (2017)

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Heiss, 1938

Arzone (1972)

Arzone (1972)

Arzone (1972)

Kumar et al, 1987

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Kumar et al, 1987

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Dixon, 1960

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dussaix (site web)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska, 1962

Dixon, 1960

Bhatia (1939)

Scott (1939)

Bhatia (1939)

Dusek & Laska, 1967

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Bhatia (1939)

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1988b)

Metcalf (1916)

Metcalf (1916)

Metcalf (1916)

Eupeodes nuba (Wiedemann), 1830

Orengo-Green, José, Casiraghi, Alice, Pérez Hidalgo, Nicolás & Ángeles, M. (2025).

Orengo-Green, José, Casiraghi, Alice, Pérez Hidalgo, Nicolás & Ángeles, M. (2025).

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dussaix, 2013

Wolton & Luff (2016).

Ricarte et al, 2007

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Stuke, 2000

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Stuke, 2000

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dusek & Laska (1988)

Dussaix, 2013

Wolton (2016).

Ricarte et al, 2007

Ricarte et al, 2007

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1991) and MacGowan, 1997

Bartsch et al (2009)

Rotheray (1991)

Krivosheina (2003b)

rufa (Fallen) 1817

= H. ingrica

Krivosheina (2003)

Bagachanova (1990)

Hartley (1961)

Bagachanova (1990)

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Hartley (1961)

Bagachanova (1990)

Dolezil (1972)

Bagachanova (1990)

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dussaix, 2013

Tawfik et al (1974)

Kumar et al, 1987

Lal & Gupta (1953)

Lal & Gupta (1953)

Kumar et al, 1987

Lal & Gupta (1953)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mitchell, 1962

Mitchell, 1962

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mitchell, 1962

Mitchell, 1962

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Mitchell, 1962

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Lejogaster tarsata (Meigen), 1822 L.splendida

Rotheray (1994)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray, (1988b)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1967)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Dixon, 1960

Hartley (1961) // Maibach & Goeldlin (1989)

Krivosheina, 2002

Maibach & Goeldlin (1989)

Krivosheina, 2002

Krivosheina, 2002

Maibach & Goeldlin (1989)

Krivosheina, 2002

Krivosheina, 2002

Maibach & Goeldlin (1989)

Dussaix (site web)

Sanchez-Galvan et al., 2017

Ricarte et al, 2007

Sanchez-Galvan et al., 2017

Ricarte et al, 2007

Lauriaut & Lair, 2018

Svivova et al (1999)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1995)

Krivosheina, 2002

Krivosheina, 2002

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1995)

Krivosheina, 2002

Krivosheina, 2002

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Láska, Mazánek & Bičík, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1988a)

Rotheray (1994)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1988a)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska, 1967 and Láska, Mazánek & Bičík, 2013

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Smith, 1989

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert, 2011

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Hennig, 1952

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Metcalf (1916)

Metcalf (1916)

Heiss, 1938

Metcalf (1916)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1967)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Heiss, 1938

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Láska, Mazánek & Bičík, 2013

Heiss, 1938

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Láska, Mazánek & Bičík, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Morris, 1998

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Dixon, 1960

Dussaix, 2013

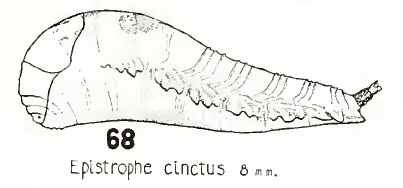

(Heiss, 1938, as Epistrophe cincta and E.triangulifera, according to Vockeroth, 1992)

Dixon, 1960

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974 // Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Scott (1939)

Scott (1939)

Dussaix (2013)

Dixon, 1960

Dixon, 1960

Scott (1939)

Scott (1939)

Merodon aeneus Meigen, 1822

Preradovic et al (2018)

Preradovic et al (2018)

Langlois D & Speight M. C. D. (2022)

Langlois D & Speight M. C. D. (2022)

Preradovic et al, 2018

Andric et al., 2014

Andric et al., 2014

Preradovic et al, 2018

J.J. Orengo-Green, A. Ricarte, M. Hauser et al., 2024

J.J. Orengo-Green, A. Ricarte, M. Hauser et al., 2024

J.J. Orengo-Green, A. Ricarte, M. Hauser et al., 2024

J.J. Orengo-Green, A. Ricarte, M. Hauser et al., 2024

Colorado Insect of Interest

Rotheray (1994)

Smith, 1989

Morgan, 1970

Dusek & Laska (1961) // Dusek & Laska (1960a) and Heiss, 1938 and Hennig, 1952

Rotheray & Gilbert, 2011

Stuke, 20000

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Doucette et al, 1942

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Ricarte et al., (2017)

Ricarte et al (2008)

Ricarte et al (2008)

Preradovic et al, 2018

Aracil et al. (2024)

Aracil et al. (2024)

Aracil et al. (2024)

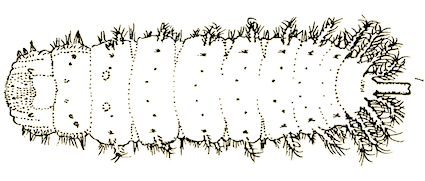

Hartley (1961) M. eggeri

Dixon, 1960 M. eggeri

Rotheray (1994)

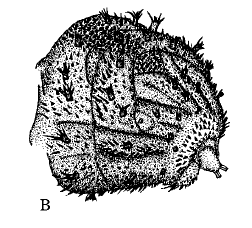

Reemer M, Stahls G (2013) Generic revision and species classification of the Microdontinae (Diptera, Syrphidae). ZooKeys 288: 14213. doi: 10.3897/Z00keys.288.4095 : M.analis = M.eggeri

Dussaix, 2013

Reemer et (2009)

Comme M. eggeri

Barr (1995) M. eggeri

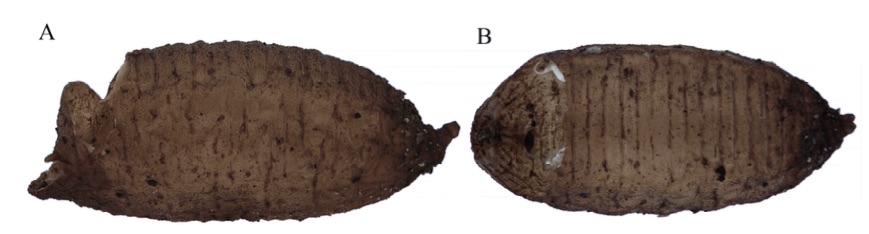

Scarparo et al. (2020)

Hartley (1961)

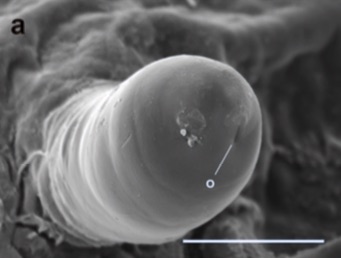

Andries (1912) & Schmid, 2004 Comme M. eggeri

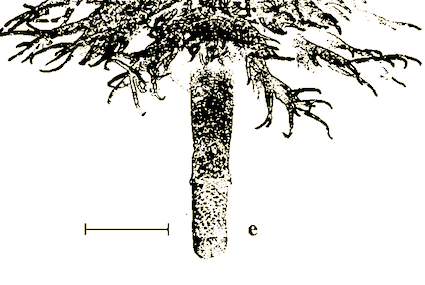

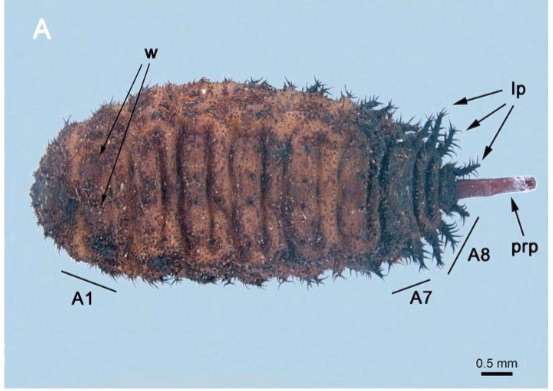

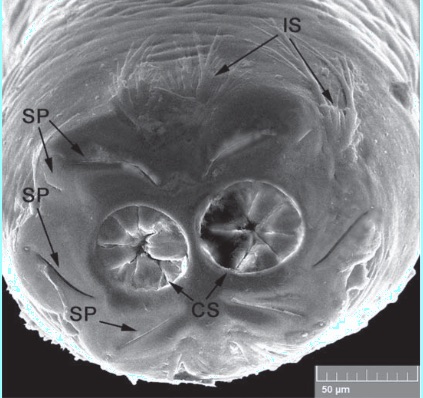

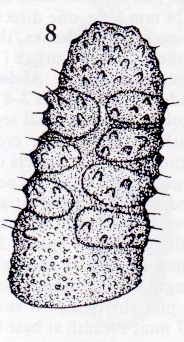

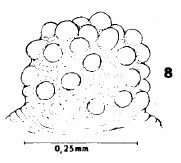

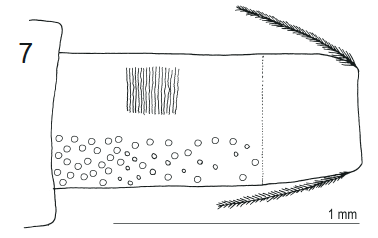

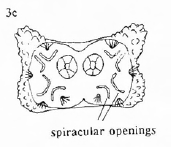

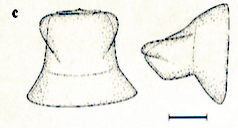

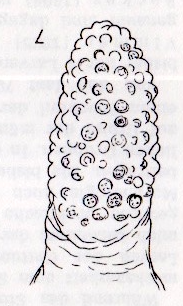

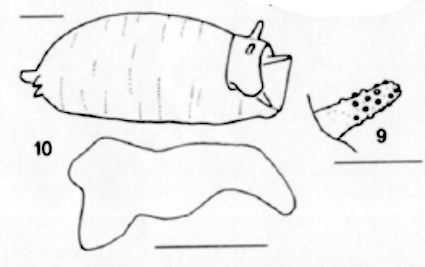

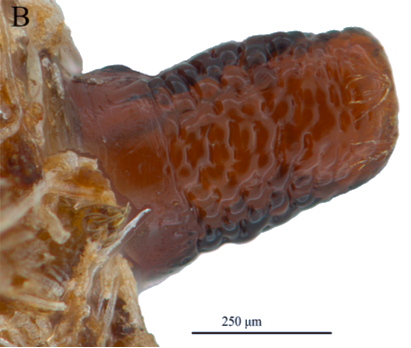

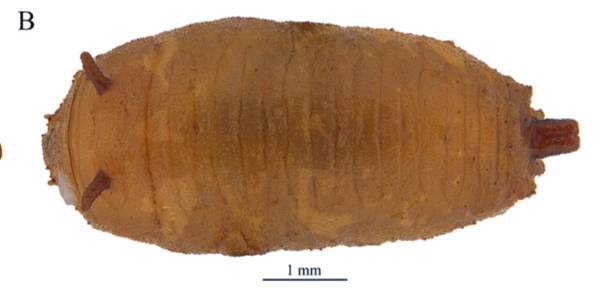

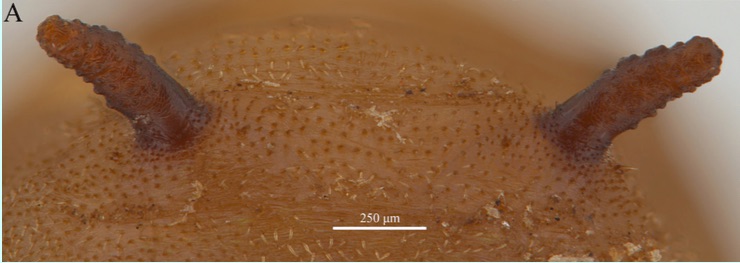

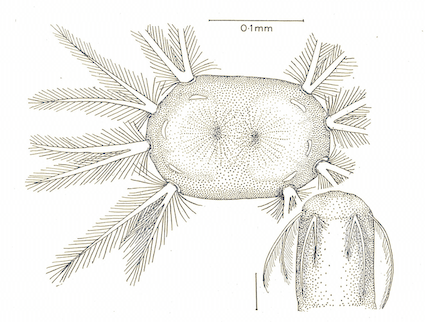

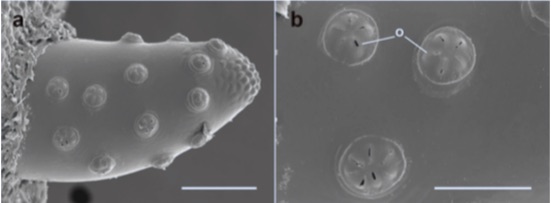

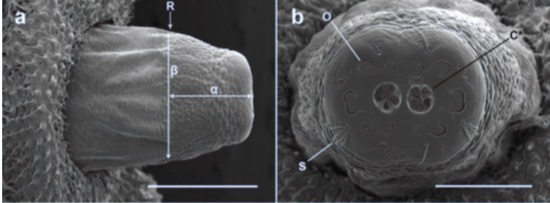

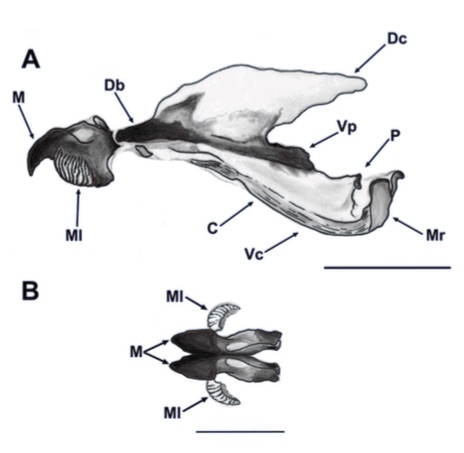

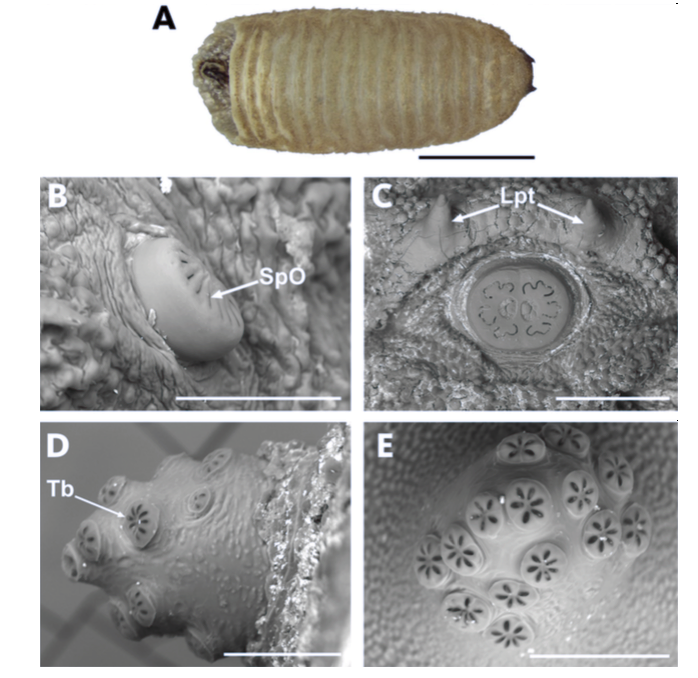

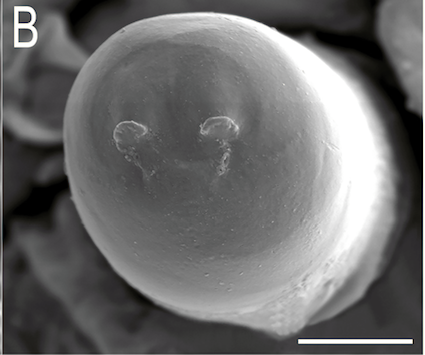

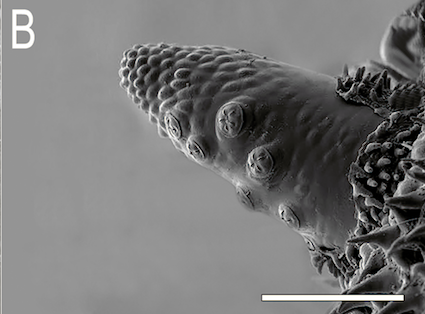

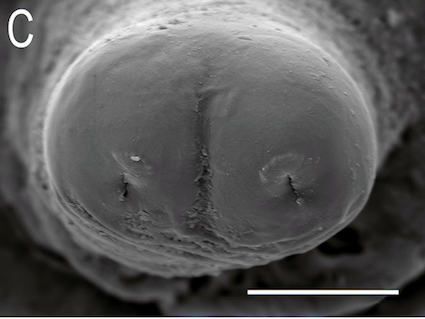

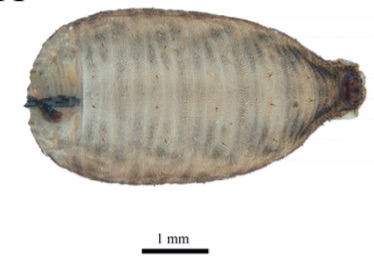

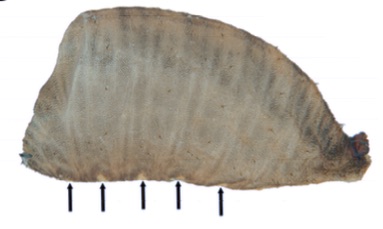

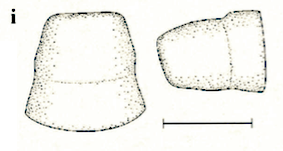

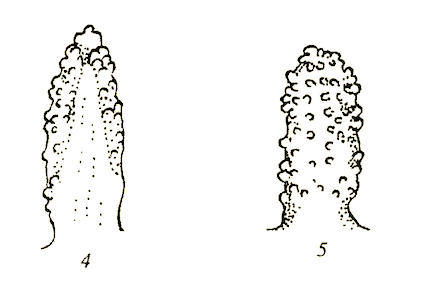

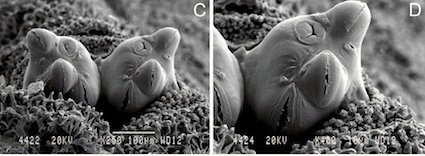

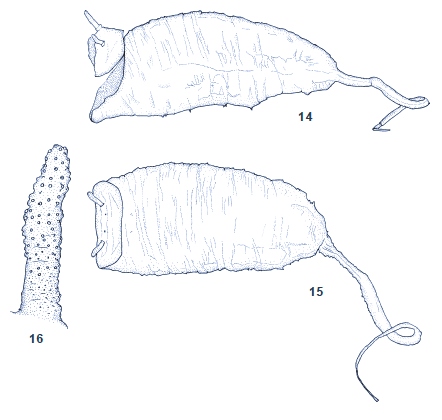

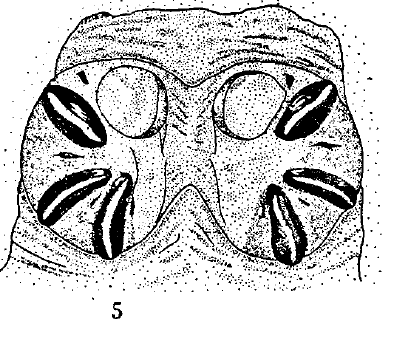

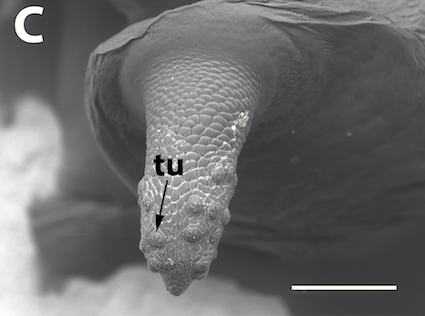

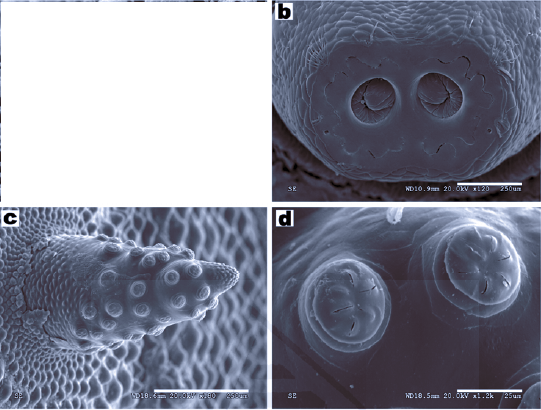

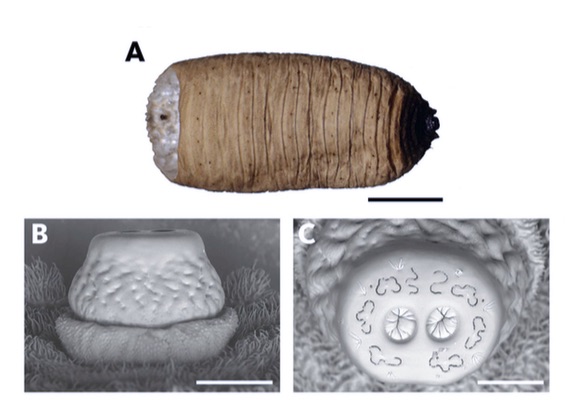

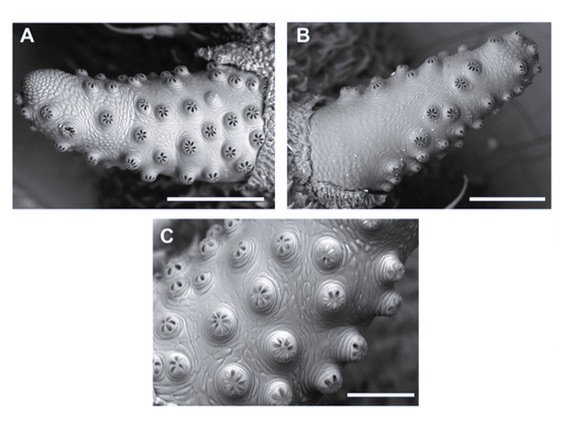

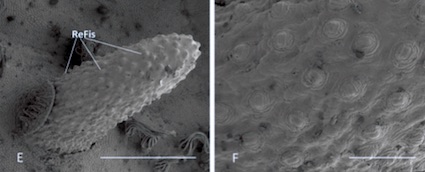

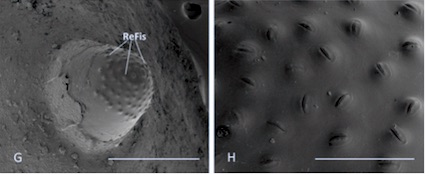

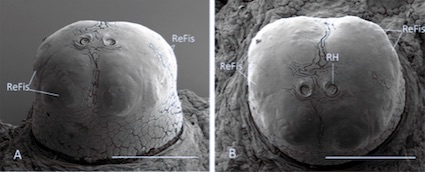

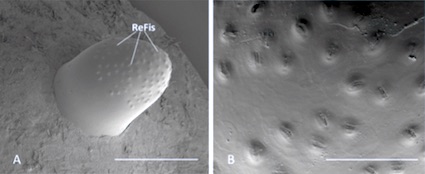

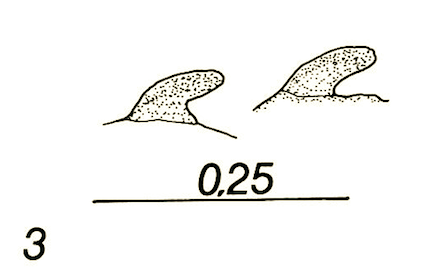

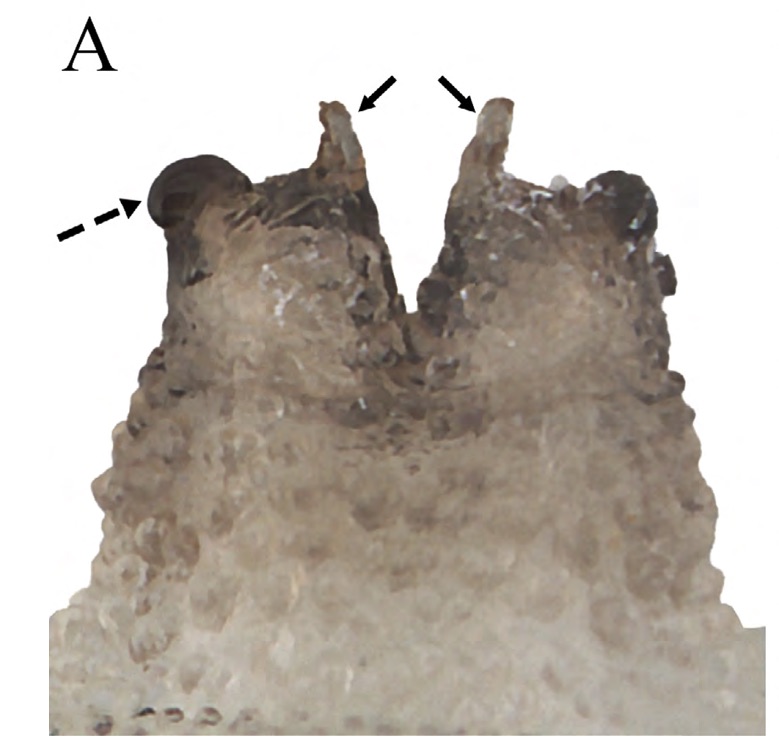

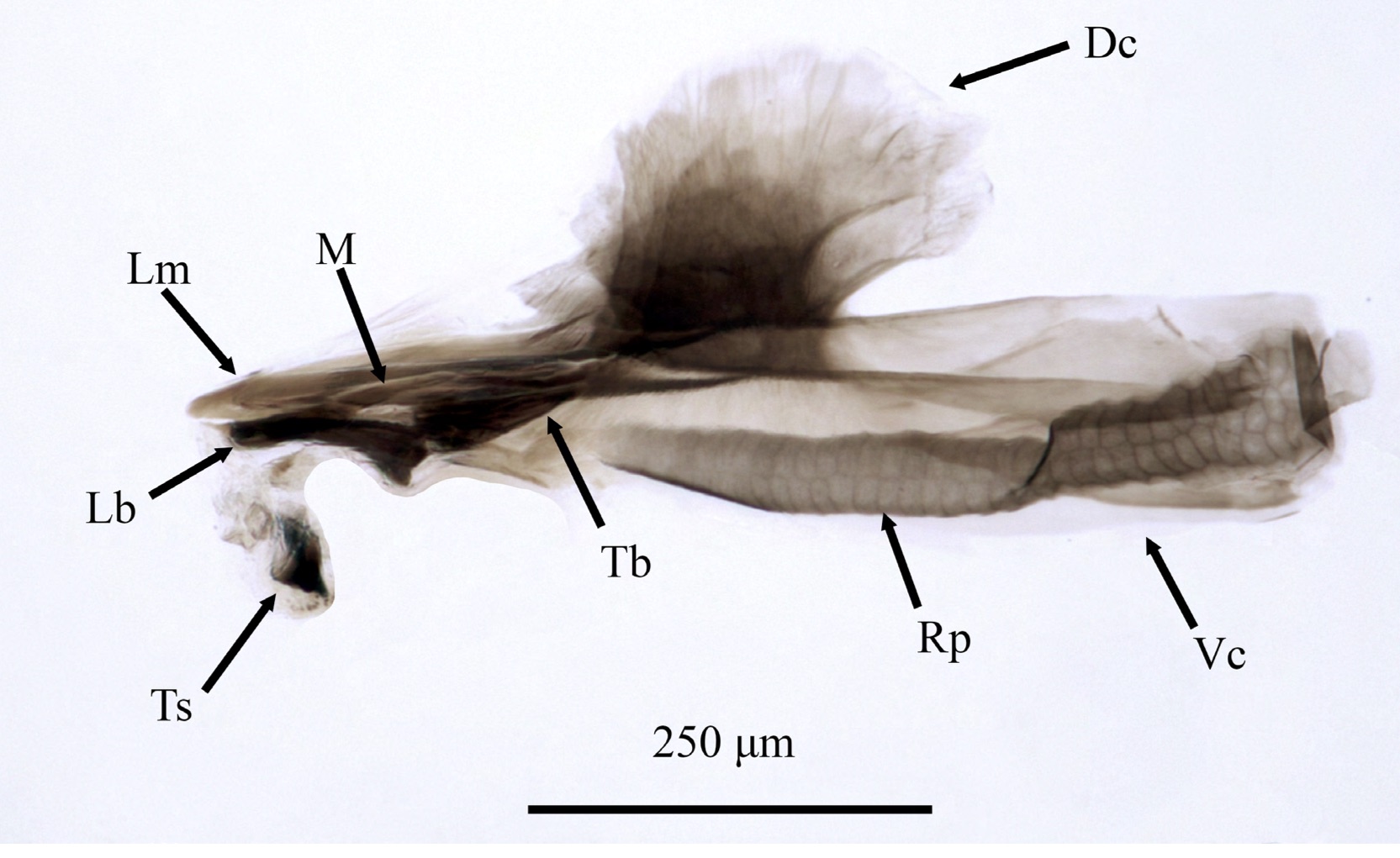

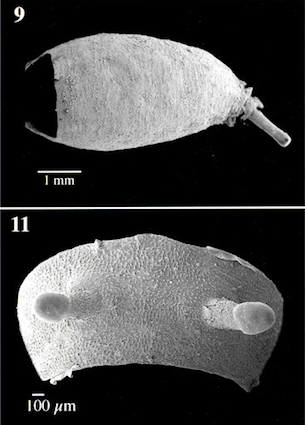

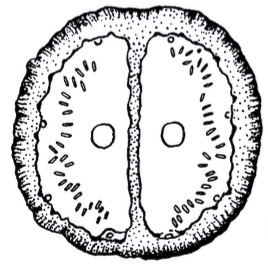

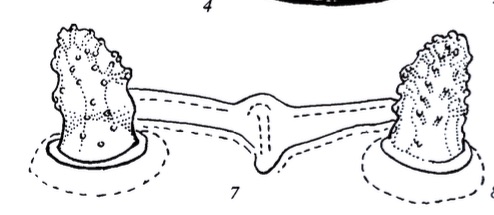

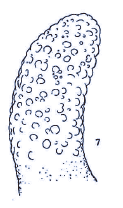

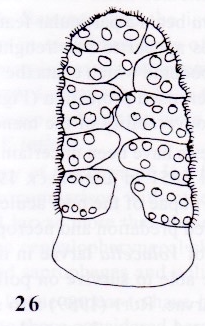

Scarparo et al. (2020): Anterior spiracular tubercles of puparia

Dussaix et al (2007)

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Dixon, 1960

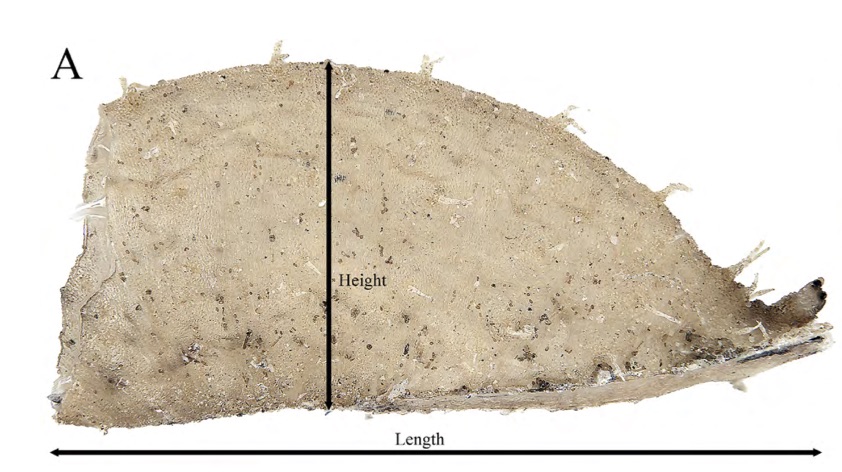

Scarparo et al. (2020)

Rotheray (1991)

Scarparo et al. (2020): Anterior spiracular tubercles of puparia

Scarparo et al. (2020)

Schmid, 2004

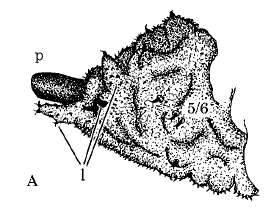

Andries (1912) // Schmid, 2004 comme Microdon eggeri var. major

Dussaix et al (2007)

Doczkal & Schmid (1999)

Doczkal et al, 2016

Doczkal & Schmid (1999)

Scarparo et al., 2017

Rotheray (1994)

Andries (1912) Like M. rhenanus

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Doczkal & Schmid (1999)

Schmid, 2004

Barr (1995)

Andries (1912)

Scarparo et al., 2017

Scarparo et al. (2020)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999

Beuker, 2004

Andries (1912) M. mutabilis / M. rhenanus

Scarparo et al. (2020) : Anterior spiracular tubercles of puparia

Scarparo et al., 2017

Gammelmo & Aarvik, 2007

Witek et al., 2012

Neumeyer & Dobler Gross, 2012

Schmid, 2004

Scarparo et al. (2020)

Beuker, 2004

Schönrogge et al., 2002a

Scarparo et al. (2020) : Anterior spiracular tubercles of puparia

Gammelmo & Aarvik, 2007

Gammelmo & Aarvik, 2007

Neumeyer & Dobler Gross, 2012

Beuker, 2014

Orengo-Green J.J. et al. (2023)

Orengo-Green J.J. et al. (2023)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek, J. & Laska, P. (1959)

Reemer et (2009)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Dusek & Laska (1960a) // Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dussaix, 2013

Ricarte et al, 2007

Ricarte et al, 2007

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1960b) // Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Rotheray & Gilbert, 2011

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix, 1913

Ricarte et al., 2007

Rotheray (1991)

Svivova et al (1999)

Svivova et al (1999)

Dussaix, 1997

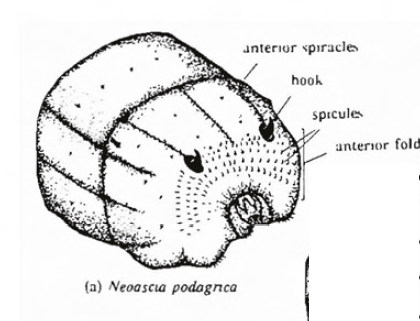

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

= N. floralis

Lundbeck (1916)

Lundbeck (1916)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Hartley (1961) // Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Dussaix, 2013

Bartsch et al (2009)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Dusek & Laska (1962)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Dussaix (site web)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1993

Dusek & Laska (1960)

Dusek & Laska (1960)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960)

Dusek & Laska (1960)

Dusek & Laska (1960)

larva predatory on adelgid plant bugs; described and figured by Delucchi et al (1957), from larvae collected on Abies. The species has also been reared from larvae found feeding on coccids on Populus and aphids on Malus (Evenhuis, 1959). The morphology of the chorion of the egg is figured by Kuznetzov (1988).

Delucchi et al (1957)

Delucchi et al (1957)

Rotheray (1994)

`

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1994)

Rotheray & Sarthou (2007)

Rotheray & Sarthou (2007)

Rotheray & Sarthou (2007)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Heiss, 1938

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Heiss, 1938

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Orengo-Green et al, 2025

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix (site web)

Orengo-Green et al. 2024

Orengo-Green et al. 2024

Orengo-Green et al. 2024

= P. majoranae

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Heiss, 1938

Dixon, 1960

Heiss, 1938

Heiss, 1938

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1994)

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

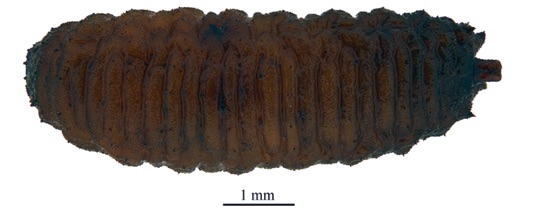

Rotheray & Gilbert (2011)

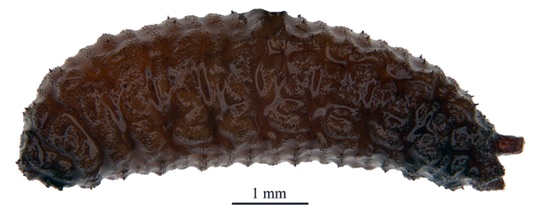

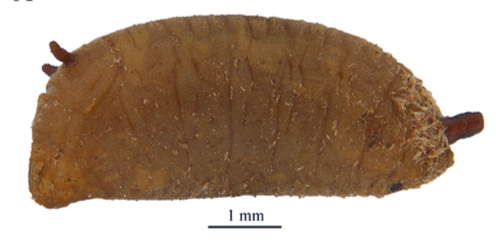

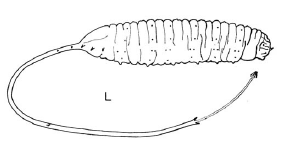

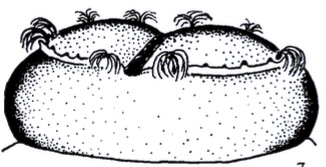

Diapaused Larva

Schneider (1953)

Foster R. (2020)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Rotheray (1987)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Rotheray (1994)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Hartley (1961) and Dolezil (1972)

Dolezil (1972)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Ståhls G (2024)

Pelecocera lugubris Perris, 1839

ou

Pelecocera lusitanica (Mik), 1898)

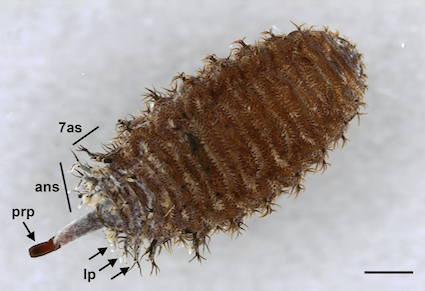

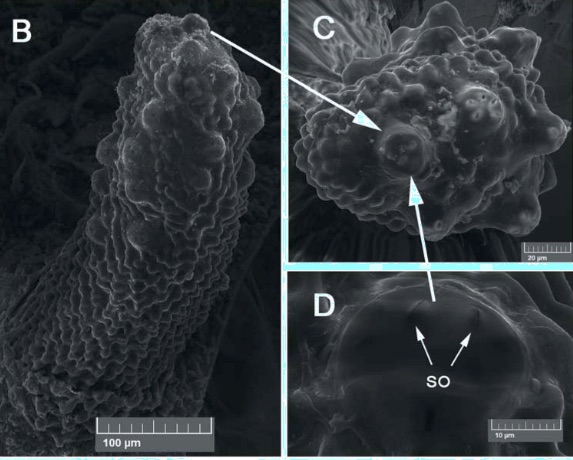

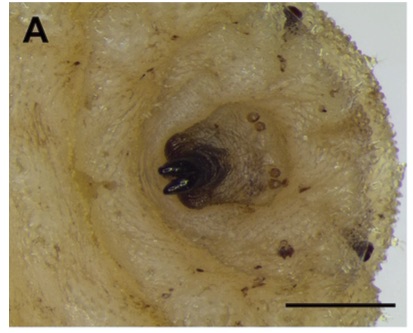

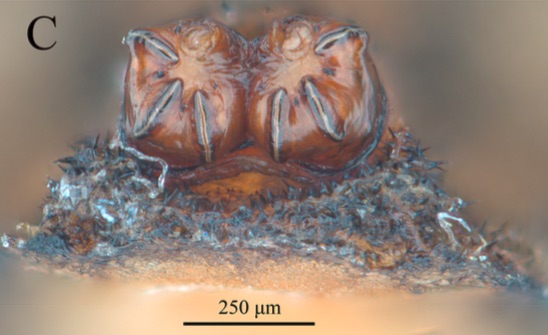

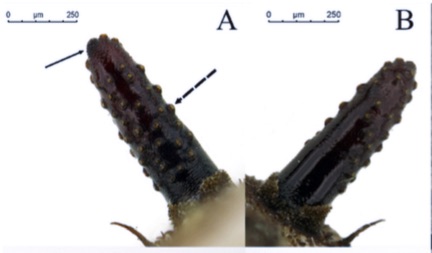

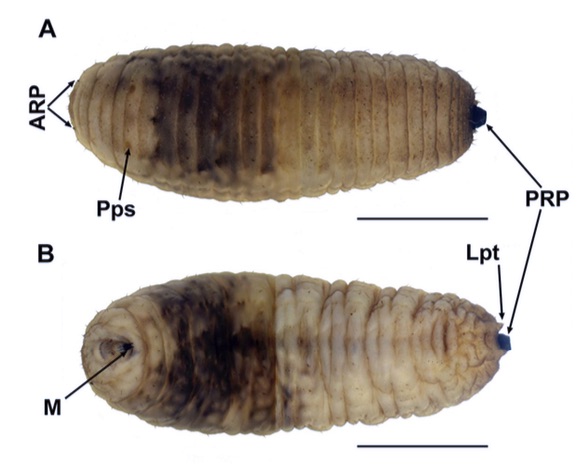

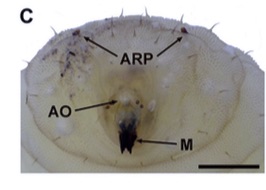

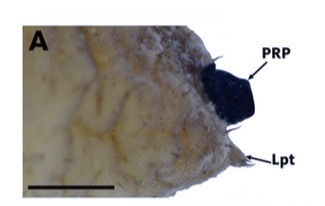

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

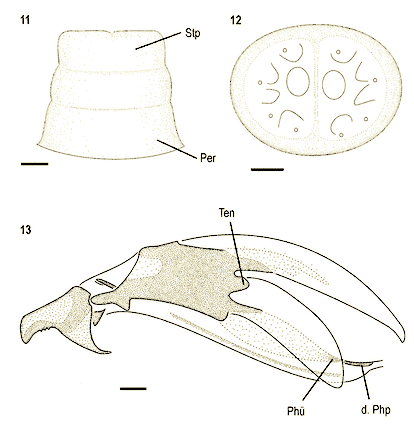

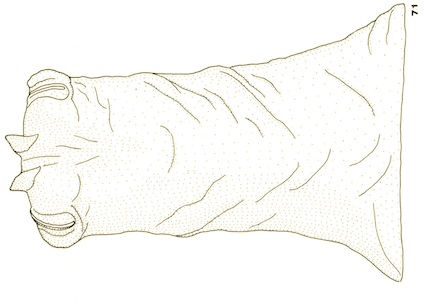

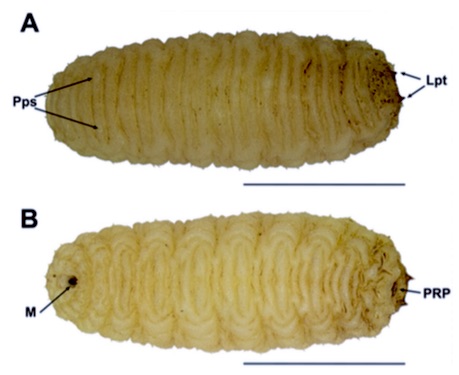

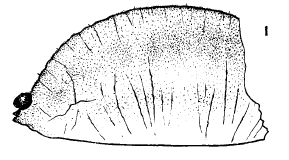

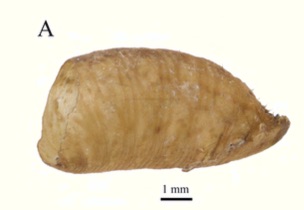

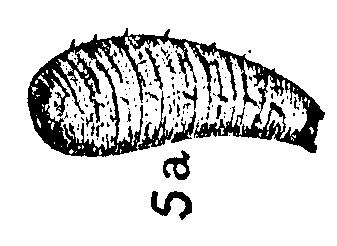

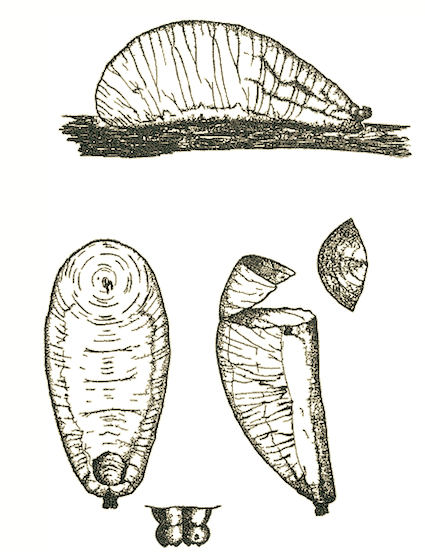

Pré-Pupe

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

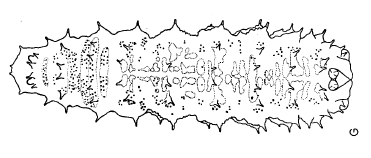

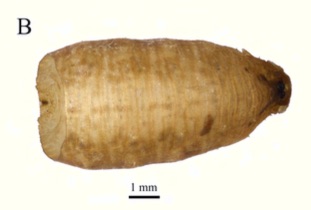

Second stage larva (L2)

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

Second stage larva (L2)

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

Ståhls G (2024)

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

Orengo-Green, J.J.; Marcos-García, M.Á; Carstensen, L.B.; Ricarte, A. 2024

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959) and Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1987)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Dussaix, 2013

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

= P. varipes

Dixon, 1960

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Dixon, 1960

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1988)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray & Dobson (1987)

Rotheray & Dobson (1987)

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dixon, 1960

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1997)

Rotheray (1997)

Rotheray (1997)

=P. ovalis

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

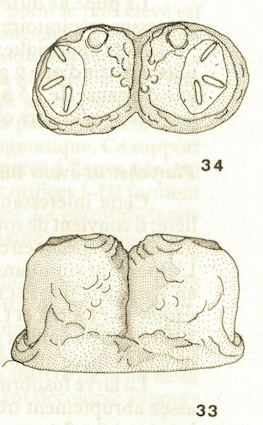

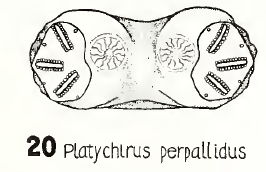

Platycheirusperpallidus Verrall, 1901

Maibach & Goeldlin (1991a)

Maibach & Goeldlin (1991a)

Heiss, 1938

Maibach & Goeldlin (1991a)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1988a)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Reemer et al (2009)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Bhatia (1939)

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1998)

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Dixon, 1960

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (1994)

Speight, 1986b

Speight, 1986b

Rotheray (1991)

Stuke, 2000

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Stuke, 2000

Speight, 1986b

Kassebeer et al. (1998)

Kassebeer et al. (1998)

Kassebeer et al. (1998)

Rotheray (1994)

Coe (1942) and Coe (1953)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999) // Hennig, 1952

Coe (1942) and Coe (1953) and Dixon, 1960 // Coe (1942)

Hartley (1963)

Stuke, 2000

Coe (1953)

Coe (1942)

Rotheray & Rotheray (2021)

Grunin (1939)

Rotheray & Rotheray (2021)

Hartley (1961)

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Maibach & Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1994

Hartley (1961)

Kuznetzov & Daminova (1994)

Kuznetzov & Daminova (1994)

Laska et al (2006)

Kuznetzov & Daminova (1994)

Laska et al (2006)

Laska et al (2006)

Dussaix (site web)

Bhatia (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Brauns, 1953

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Heiss, 1938

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Laska et al (2006)

Dussaix, 2013

Laska et al (2006)

Brauns, 1953

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Scott (1939)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Laska et al (2006)

Scott (1939)

Rotheray (1994)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1963)

Hartley (1961)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1995)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1995)

Kuznetzov & Kuznetzova (1995)

= S. menthastri

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1987)

Dusek & Laska (1960b) and Láska & Bicík, 2005

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Bhatia (1939)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Scott (1939)

Dussaix, 2013

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dusek & Laska (1961) and Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Hartley (1963)

Dussaix (site web)

Hartley (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Goudsmits, 2009

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix (site web)

Dussaix, 2007

Dussaix (site web)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Dussaix, 2007

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Rotheray et al. (2006)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-García (2000)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-García (2000)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-García (2000)

Dussaix, 2013

Smith, 1989

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Hodson (1931) and Morgan, 1970

Bartsch et al (2009)

Heiss, 1938 and Hennig, 1952

Hartley (1961)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-García (2000)

Heiss, 1938

Metcalf (1916)

Hodson (1931)

Pérez-Bañón & Marcos-García (2000)

Dussaix, 2013

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (1994)

Bhatia (1939)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Bhatia (1939)

Pavel Láska, Libor Mazánek & Vítězslav Bičík, 2013

and Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Nielsen et al, 1954

Henning, 1952

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Scott (1939)

Goeldlin de Tiefenau, 1974

Dussaix, 2013

Metcalf (1911)

Dixon, 1960 // Metcalf (1911)

Nielsen et al, 1954

Scott (1939)

Metcalf (1916)

Metcalf, 1916

Dussaix, 2013

Mitchell, 1962

Brauns, 1953

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dixon, 1960 // Mitchell, 1962

Mitchell, 1962

Brauns, 1953

Dussaix, 2013

Krivosheina, M.G. (2003b)

Krivosheina, M.G. (2003b)

Heqvist (1957)

Heqvist (1957)

Krivosheina & Mamayev (1962)

Heiss, 1938

Krivosheina and Mamayev (1962)

Heiss, 1938 and Hennig, 1952

Metcalf (1933)

Krivosheina, (2003a)

Heiss, 1938

Krivosheina, (2003a)

Krivosheina and Mamayev (1962)

Rotheray (1994)

Stammer (1933)

Dusek & Laska (1960a) // Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1997)

Van Steenis et al (2018)

= T. ochrozona

Van Steenis et al (2018)

Van Steenis et al (2018)

Sedlag (1967

© Leif Bloss Carstensen

ORENGO-GREEN et al, 2024

ORENGO-GREEN et al, 2024

ORENGO-GREEN et al, 2024

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1994)

Decleer & Rotheray (1990)

Decleer & Rotheray (1990)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Smith, 1989

Rotheray (1999)

Rupp (1989)

Monfared et al, 2013

Rotheray (1999b)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray (1999b)

Karp, 2015

Rotheray (1994)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Rupp (1989)

Foster, 2019

Smith. 1989

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Hartley (1961) // Dusek & Laska (1961)

Rotheray (1999b)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Foster, 2019

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1999b)

Rotheray (1994)

Rupp (1989)

Rotheray (1999b)

Dusek & Laska (1960a) // Dusek & Laska (1961)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray & Gilbert (1999)

Rotheray (1999b)

Dusek & Laska (1961)

Reemer et (2009)

Rotheray (1999b)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (1999b)

Geoff Wilkinson et al (2020)

Rotheray (1994)

Santolamazza et al, 2011

Carstensen, 2015

Rotheray (1994) // Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Dusek and Laska (1967)

Dusek & Laska (1959)

Dusek & Laska (1960a)

Santolamazza et al, 2011

Lyon, 1968

Carstensen, 2015

=X. festivum

Speight (1990)

Dussaix, 2013

Speight (1990) and Rotheray & Gilbert (1989)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Rotheray (2004)

Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Rotheray (2004)

Dusek & Laska (1959) and Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Dusek & Laska (1960a) and Dusek & Laska (1960b)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray & Stuke, 1998

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (2004)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (2004)

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (2004)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (2004)

Hartley (1961)

Dussaix, 2013

Rotheray (1994)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (1991)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Rotheray (2004)

Hartley (1961)

Rotheray (2004)